Public bicycle scheme: Madrid and Buenos Aires jump on the bandwagon of environmental-friendly cities

Transport is a key enabler of economic activity and social connectivity. While providing essential services to society, transport is also an important part of the economy and it is at the core of a number of major sustainability challenges, such as climate change, air quality, safety, energy, security and efficiency in the use of resources (EC 2011: Transport White Paper) [1].

Motorized mobility, and especially the widespread use of private cars, significantly contribute to fossil fuel consumption. Not surprisingly, 75% of global oil is consumed in urban areas, especially in the metropolis of western countries (Heinberg, 2006) [2].

The current urban model based on maximizing transport and the use of private cars has already clashed with the biophysical limits of the planet. Regional and National climate change policies, air pollution, premature deaths due to car accidents, among others, are many of the challenges that city councils are facing. On top of it, the use of private cars has failed to fulfill the promise to facilitate an easy and quickly urban travel.

Many cities around the world are aware of the aforementioned challenges and the need to recover a human scale city, returning to the idea of neighborhoods, proximity and thus creating closeness. These cities have been fostering walking and cycling for many decades, while restricting motorized mobility.

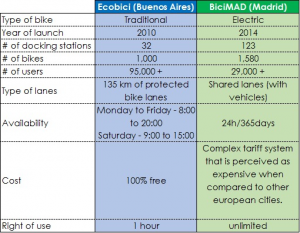

Following the track of the most environmental-friendly cities, Buenos Aires and Madrid are two of the latest capitals to boost the bike by launching in 2010 and 2014, respectively, a public bicycle scheme that include, among others, the creation of bike lanes, public bikes distributed around the city and incentives to promote bicycle-buying.

The main characteristics of the incorporation of public bikes both in Buenos Aires and Madrid are as follows:

At first, in both cities this was unpopular, especially among car drivers, mainly because bikes were seen solely as tools for exercise and leisure. However, public opinion seems to be warming the idea, partly because cycling is a quicker way to get about the capitals. In order to have a better understanding of the impacts of the bicycle scheme both in Buenos Aires and Madrid, below we discuss further some of the key elements of its implementation.

Ecobici in Buenos Aires

As “porteñas” as tango, 4 years after implementation the public yellow bicycles have become part of the urban landscape. In a city dominated by buses and taxis, cyclist have seen their efforts rewarded after years claiming for a space in the public transportation system. From 3 docking stations, 72 bicycles and 100 trips per day in 2010 to 32 docking stations, 1.000 bikes and over 95.000 registered users in 2014.

This, in part, justify the ambitious future plan prepared by the city council: to expand the system to 200 stations with at least 3.000 bicycles and a new hybrid system where manual and automatic stations coexist to provide a better user experience, improve real time information while reducing waiting times at stations.

What makes Ecobici successful? The government of Buenos Aires believes it is mostly due to the absence of tariffs and docking stations assisted by employees whom receive users and guarantee the return of the bicycles. However, it is worth mentioning other incentives that made the bicycle system attractive:

- Buenos Aires is one of the largest cities in the world (population over 12,7 million in the metropolitan area [3]) and the bus transportation system is far from being reliable. Although los colectivos (the common name for buses in Argentina) are considered a public system, the buses are privately own and the service vary on each company. Buses stops are not easy to locate, the itinerary and schedule is often not clear and the system containing 110 different lines makes the entire bus network incomprehensive for many citizens.

- Before Ecobici was implemented, 1 every 3 citizens had a bicycle and they toured the city often sharing lanes with cars and buses, aggravating traffic congestion and causing accidents.

- Streets and sidewalks in Buenos Aires are wide and spacious which allowed the construction of protected bike lanes.

- Ecobici is easy to use and accessible. Only with an ID and a proof of address one is ready to ride.

- Ecobici is framed in a comprehensive strategy that is not only limited to the public bike system. Rather, the city of Buenos Aires adopted a holistic approach to sustainable mobility through a wide range of investments in public transport (such as Metrobus), infrastructure and road safety, among others.

Based on the above, evidence suggests that Ecobici has arrived to stay.

BiciMAD in Madrid

Although the public transportation system of Madrid is among the best in the world, the challenge lies in seeking future transfer of travelers from private car to non-motorized transport. In this sense, the city of Madrid inaugurated BiciMAD in June 2014, a public bicycle system in which each of its 1,580 bicycles is electrical, distributed in 123 docking stations, covering approximately 30 hectares in the city center. A future enlargement is expected in 2015 by incorporating 400 bicycles and 35 additional docking stations in the districts of Chamberi and Tetuan, located in the north of the Spanish capital.

The electrical nature of the bicycles is a crucial factor in favor of BiciMAD as it makes it more attractive to users by allowing greater flexibility in the traffic lights and crossings, as well as a way to overcome the slopes within the city. On the other hand, the absence of protected bike lanes and the complex tariff system created some uncertainty around the feasibility of its implementation and acceptance among users. In practice, the absence of segregated bike lanes has caused cyclist to circulate in shared lanes with cars where the maximum speed has been reduced to 30 km/h. The overall impact is positive as the traffic flow and the circulation speed were reduced, causing less congestion. The fact that bicycles are electrical and can reach higher speeds has facilitated its integration between cars. In connection with the tariff system, although a payment is required to use BiciMAD, it is particularly cheap for madrileños (not so for tourist and occasional visitors as tariffs differ) and allows large amount of savings on gas, parking, and time spent on traffic jams which discourage motorized transport, especially the private car. As a result, the premise that the payment system was a weakness has not been met. Low prices has encouraged users and attracted new people to cycling.

Conclusion

Ecobici has helped Buenos Aires to obtain the 2014 Sustainable Transport Award. The city received this international honor for improvements to urban mobility, reducing CO2 emissions and improving safety for pedestrians and cyclists.

In the case of Madrid, the number of users of BiciMAD has significantly increased since implementation, encouraging the use of private bicycles and creating a positive impact on traffic jams. An initial enlargement is already approved for 2015, and future enlargements are likely to occur until the scheme covers the totality of Madrid inside M-30, subject to demand.

Regardless the model of implementation, the truth is that every city adapts cycling according to its needs and characteristics. The key is to adopt a more sustainable mobility approach and both Buenos Aires and Madrid are in the right path to success.

References:

[1] European Commission (2011). White Paper on transport: roadmap to a single European transport area – towards a competitive and resource-efficient transport system. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2011.

[2] Heinberg, R.: Se acabó la fiesta. Guerra y colapso económico en el umbral del fin de la Era del Petróleo. Barrabes Editorial, 2006.

Morales Carvallo, L., Leon, P., Ramis, I., Bravo, P. (2014). BiciMAD y el auge de la bicicleta en Madrid. Congreso Nacional del Medio Ambiente 2014.

Gartner, A. (2013). El sistema mas humano de biciletas compartidas esta en Buenos Aires. Grupo del Banco Mundial.

.png)

].gif)

.png)

].png)

].png)

].png)

.png)

].png)

.png)